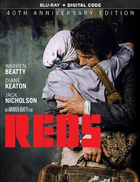

Reds [Blu-Ray]

|

By any stretch of the imagination, it is either an outright miracle or testament to his power in Hollywood at the end of the 1970s (or maybe a little of both) that Warren Beatty was able to produce and direct Reds, his romantic epic about the Bolshevik Revolution and the birth of the American Left. Reds was released a year into Ronald Reagan's first Presidency, a time of increased conservatism in the United States and, more importantly, heightened tensions with the great "Evil Empire," as Reagan called the Soviet Union two years later in his famous speech to the National Association of Evangelicals. Yet, somehow Beatty managed to not only get the film financed by a major Hollywood studio (Paramount), but with a massive $35 million budget and an enviable cast of A-list actors. It was fortunate that he was able to secure financing when he did, because while the film was in production Michael Cimino's ambitious $40 million Marxist-Western Heaven's Gate bombed theatrically and critically and literally toppled United Artists. Beatty had wanted to make a film about the journalist and socialist agitator John Reed, one of only two Americans to be buried in the Kremlin wall, since the mid-1960s, and over the years the material had seeped into his bones. As a committed left-wing activist, Beatty saw much to admire in Reed and the path he forged through early-20th-century American politics, and he likely identified with Reed's struggles as both an artist and a political figure. In also playing Reed, Beatty ran the risk of collapsing the distinction between filmmaker and subject, but one of the film's strengths is that he doesn't lionize Reed (or himself, for that matter) into the cinematic equivalent of a bronze statue. Reds is nothing if not passionate, intense, and—for a Hollywood film, anyway—respectful of historical detail and accuracy. Like all Hollywood productions that paint history onto the great silver canvas, Reds takes a few liberties and cuts a few corners, but for the most part historians agree that it gets the basic story right. Beatty's screenplay, which he cowrote with British playwright Trevor Griffiths (and was given some uncredited polishing by Robert Towne and Elaine May), takes the Gone With the Wind / Dr. Zhivago approach to history by setting a florid, albeit unconventional, romance against the backdrop of social upheaval. Shot in luscious shades of amber and burnished gold by cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (1900, Apocalypse Now) on location around the world, Reds has all the visual trappings of the romantic epic, and Dede Allen and Craig McKay's editing keeps the story moving steadily along. The 3-hour and 15-minute film is divided into two parts, separated by an intermission. The first half establishes the main characters and focuses on the events leading up to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, while the second half deals with the development of the Left in the United States, particularly the squabbling among various factions of the Socialist Party and the struggle to develop an American communist party. The emotional strand that connects the two halves is John Reed's relationship with Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton), a burgeoning feminist writer whom Reed meets when she is still conventionally married to a dentist in Portland, Oregon. Reed lures her away with the promise of politics and art in the bohemian enclave of Greenwich Village, where she meets figures like The Masses editor Max Eastman (Edward Herrmann) and anarchist Emma Goldman (Maureen Stapleton). Louise also meets playwright Eugene O'Neill (Jack Nicholson), a close friend of Reed's who falls in love with her, thus setting up a love triangle that will persist in various ways throughout the course of the film. Louise's relationship with O'Neill brings her and Reed's proclamations of open-mindedness and the virtues of free love into question, as neither is able to resist the burn of jealousy when one of them is with someone else. Their relationship is fraught with tension, particularly because Reed is already established as a political and journalistic voice while Louise is struggling to make a name for herself; when he casually criticizes her work, thinking he is being helpful, she snaps back that the piece is exactly as she intended it. Their fights carry an intensity and hurtfulness, and at several points in the film they separate and later reunite, never able to fully part from one another. Nevertheless, the film is frequently unfair to Louise, characterizing her as being politically and emotionally in over her head. Especially in the early scenes, Beatty gives Reed an aw-shucks boyishness that belies his intellect and passion, while Louise is constantly catty and defensive and angry. Reed seems to have been born into greatness, while Louise struggles for notoriety, which results in her often seeming insecure and shallow, not to mention hypocritical. The film freely intermixes political and romantic passion, especially in Reed and Louise's relationship. It is of little surprise that Beatty gets pathos of both stripes out of a scene in which Reed is brought up on stage to address a group of Russian workers—his first moment of pure and direct political agitation brings tears to Louise's eyes. Yet, for all his leftist leanings, Beatty does not turn a blind eye to what eventually happened in the Soviet Union, and the sadness in Reds emanates as much from the death of socialist ideals at the hands of communist bureaucrats as it does from the struggles of Reed and Louise to maintain their lifelong love affair. In the film's final third, Beatty squeezes the old Hollywood stand-by—separated lovers—for all it's worth when Reed is forced to stay in Russia after the revolution and work as a propagandist while Louise embarks on a dangerous trip to find him, which further minimizes her character and elevates his. The historical veracity of Reds is underscored by a particularly ingenious device that is also the film's most questionable tactic. Rather than using voice-over narration or lengthy title cards to explain off-screen historical developments or to set the social context, Beatty employs interviews with various people who were, in one way or another, associated with John Reed, Louise Bryant, or any of their friends and acquaintances. Shot in intimate close-up against a plain black background, these include feminist writer Rebecca West, oft-censored novelist Henry Miller, and investigative journalist George Seldes. However, because Beatty does not give us their names at the bottom of the screen, we are forced to assume that they are important and authoritative, even if we don't know who each one is. In the credits, these interviewees are referred to as "witnesses," which is a generous term considering that most of them never knew Reed or Bryant and were, in fact, children when the film's events were taking place. Yet, they speak with authority about whatever subject is required by the narrative at that point, and their weathered, aged faces convey a sense of lived history and authority. In other words, they substantiate Beatty's take on history with little more than their presence, even if they have no credentials other than sharing Reed and Bryant's political views and lifestyle (the only witness to have been directly involved with them is the painter Andrew Dasburg, who had an affair with Bryant, which he never mentions during the film). Yet, even here Beatty thoughtfully allows for some ambiguity. While these witnesses are central not only to setting the stage for his epic, but also to validating his approach to history, Beatty opens the film with off-screen voices of several witnesses questioning their very role, with one saying "I've forgotten all about them" and another asking "Were they socialists?" In other words, Beatty drops in a seed of doubt in the midst of his otherwise affirmative take on worldwide political upheaval in the 1910s, suggesting that history is never pure, but rather always reliant on the teller. By recognizing this fact up front, albeit in a rather indirect manner, Beatty makes Reds all the richer and more meaningful because it is not static history, but rather a grenade of genuine political passion lobbed into an era of increasing conservatism and military build-up—an elegy for an ideal.

Copyright © 2021 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Paramount Home Entertainment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Africa Leader news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Africa Leader.

More Information